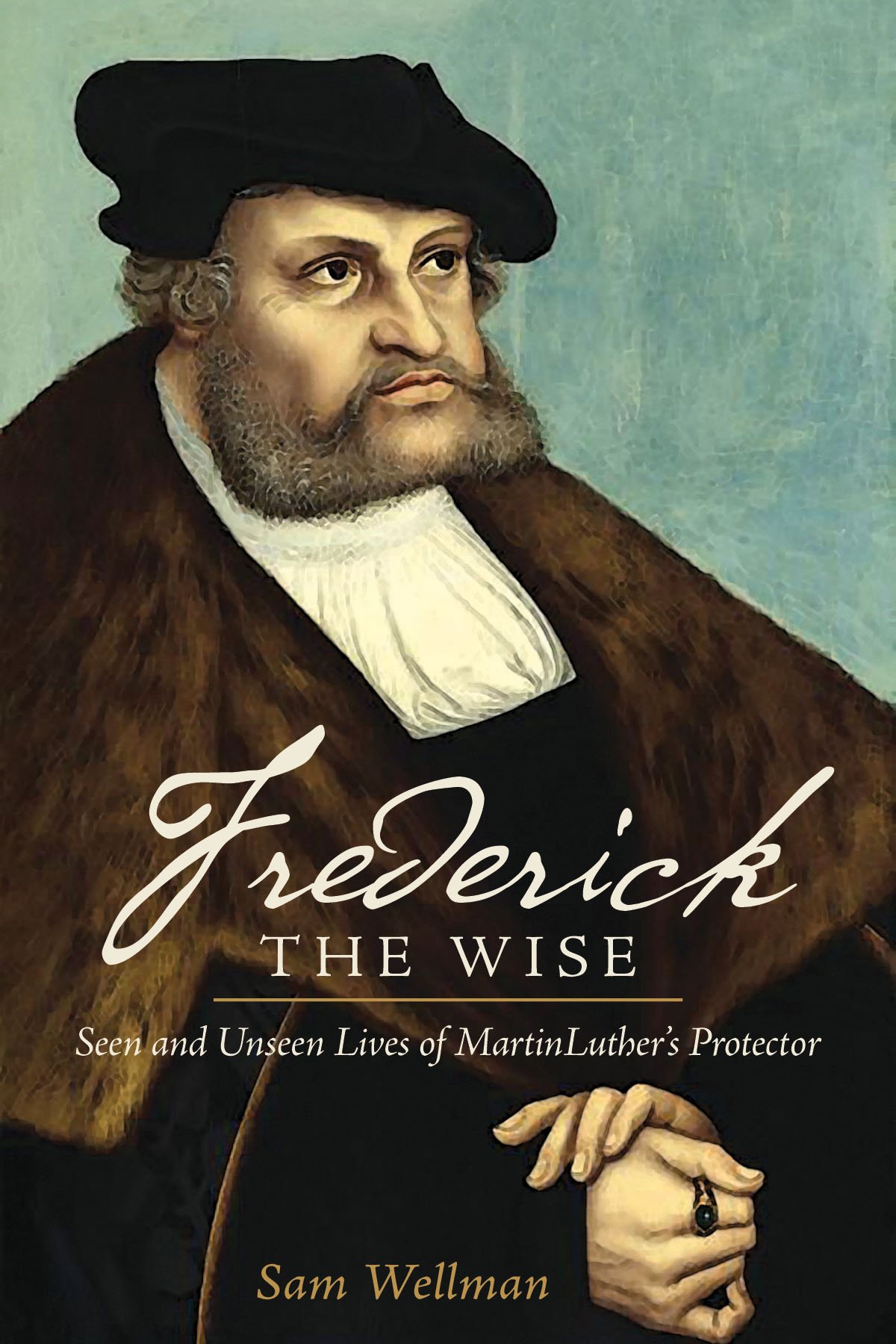

Frederick the Wise: Seen and Unseen Lives of Martin Luther’s Protector, Sam Wellman

Frederick the Wise: Seen and Unseen Lives of Martin Luther’s Protector, Sam Wellman

(Concordia Publishing House, 2015), pb., 315 pp

As soon as I began seeing announcements about this book I was excited to read it. From my engagement with Luther, Frederick the Wise had become a very intriguing character to me. I was interested to learn more about this prince who ended up playing such a significant role in the Reformation, without intending to do so. I was also intrigued by the questions I have heard raised as to whether his support of Luther was merely political, opportunist, or genuinely theological and religious. My interest was piqued even more when I read that this would be the first full-length biography of Frederick ever produced in English. So I was eager to read the book and very grateful to Concordia for a review copy.

Overall, I was very pleased to have read this book. Wellman makes accessible in English a lot of work that has been done in German, and it is obvious that he has done much work in primary as well as secondary sources. The research behind this volume is significant. It was very helpful to learn of the political divisions within Saxony prior to Frederick’s coming to power, and to see how prominent he became even early in his office.

Wellman demonstrates the prominence and influence of Frederick in the Empire and how much the Holy Roman Emperors looked to him. Wellman states, “Frederick’s influence was everywhere in the empire” (85). Many, including Luther, credited him with uniting the disparate German language into one language (85). Fredrick was regarded by all, it seems, as a man of integrity and principle. Fredrick was noted for inculcating an atmosphere of congeniality in a political setting so often filled with contention- “he had a remarkable ability to calm” (84). Unlike many of his influential peers, he was slow to pursue war, instead looking for peaceful avenues. But he did say, “I shall not start anything, but if I must fight, you shall see that it will be I who end it” (120). He was a patron of the arts and his court became a leading center for art and music. Throughout the book, Wellman sprinkles various proverbs which Frederick often used or had on display in his court.

Even the discussion of Frederick’s unofficial wife suggested character. He never married which was a real political loss. He had met and began a relationship with Anna, a woman about whom we know little. She was of noble birth, so political concerns made official marriage impractical. However, he refused to drop her in order to take a politically helpful marriage or to take such a marriage and keep Anna on the side.

Wellman describes Frederick’s efforts to compile what became an impressive collection of relics in his new church in Wittenberg. The fact that Frederick supported Luther even as he viciously attacked the business of relics, in which he had invested so much money, suggests the genuineness of his faith. (This is captured well I think in the 2003 film, “Luther”)

The book provides a helpful glimpse into the political machinations brought about by Luther’s bursting on the scene. It is a valuable reminder of how God providentially works by turning the hearts of kings or princes wherever He wills (Prov 21:1). In this section Wellman states gives his verdict on Frederick’s motivation- and provides a nicely worded contrast between Luther and Erasmus:

“Frederick and those whose judgment he most trusted were convinced that Luther was correct in his methods. Luther based his conclusions on the deepest insight into the Holy Scriptures, the only tangible source for God’s Word. It was Erasmian, except the interpreter was not a mouse muffling his voice in a cranny, but a lion who roared” (176).

“Frederick followed Luther’s teachings more and more to great cost to his own plans, even at the risk of losing his electorate. It wasn’t Luther, moreover, that Frederick was pleasing. Pleasing God, doing God’s will, was paramount” (213-14).

This book is full of very useful information. That is its strength. Its weakness, is that it feels like it hasn’t been packed very neatly or carefully but just jammed in. The flow of thought from chapter to chapter or section to section is not always clear, nor is the connectedness of one part to another in places. It tells a fascinating story but is ponderous in doing so at times. One cannot always have history that reads like a novel, but I fear that readers who are not already committed to learning about this topic might not persevere with the work. Further editorial work is likely needed.

In the end, though, I am grateful that the book has been written, and I have benefitted from it. It will be useful to anyone studying the Reformation.

I will close with this striking evaluation of Frederick from Heiko Oberman (concerning Frederick’s role in the 1519 election of Karl V):

Historians of every stripe have found only one statesman thoroughly praiseworthy: Frederick the Wise. A German and a man of integrity, he is considered to have been a staunch representative of the interests of the empire in a sea of corruptibility and national betrayal (236-37)