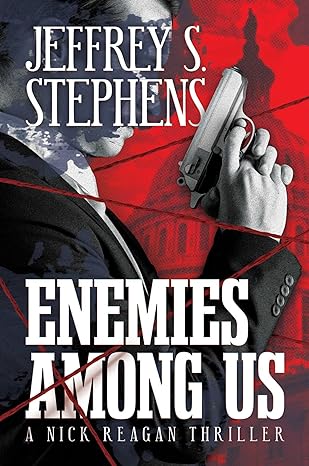

Recently I read a prepublication review copy of Jeffrey S. Stephens’ thriller, Enemies Among Us: A Nick Reagan Thriller. This is the second of his Nick Reagan books, though I have not read the first one. Regan is a CIA operative seeking to thwart terrorists who stumbles upon widespread corruption at high levels in the government.

Recently I read a prepublication review copy of Jeffrey S. Stephens’ thriller, Enemies Among Us: A Nick Reagan Thriller. This is the second of his Nick Reagan books, though I have not read the first one. Regan is a CIA operative seeking to thwart terrorists who stumbles upon widespread corruption at high levels in the government.

The book is a fun read with fast-paced action and intrigue. It is clearly aimed at a more conservative audience, as this sort of thriller tends to do. Even the name of the hero, Reagan, seems to be a nod in that direction. All of this makes it a novel well suited for me. It is also relatively clean, which is not always the case for the genre. It is sad though, that while the book is clearly marketed to conservatives, there seems to be no problem with the hero being sexually active with his girlfriend. This is an example of what several people have noted about a divide between conservatives, with a significant number not thinking traditional, biblical morality being among the things which ought to be conserved.